OUR SPONSOR

Greater Bay Shore coverage is funded in part by Shoregate, now leasing brand-new premium apartment homes in the heart of Bay Shore. Click here to schedule a tour.

Long Island’s South Shore communities are facing turbulent times due to the rapid change of traditional demographics. The people here are dealing with a rising fear of foreign threats, political divides, false news reports, contested elections, and a re-inspired Ku Klux Klan.

These events might be reminiscent of the past few months, but we’re taking you back to Suffolk County in the 1920s — and the lead-up to June 24, 1923, in Bay Shore, a remarkable day captured in the photograph above.

In 1920, Suffolk County’s population was 110,000, up from 96,000 in 1910, a 15 percent jump in a decade. The immigrant population within the county had increased from 14,650 to 23,888. Within these population shifts, Catholicism became the fastest-growing religion.

This growth faced an onslaught of fears from many local Protestants.

Rumors circulated across Long Island communities that the Catholic-affiliated organization Knights of Columbus swore oaths that waged war against American values.

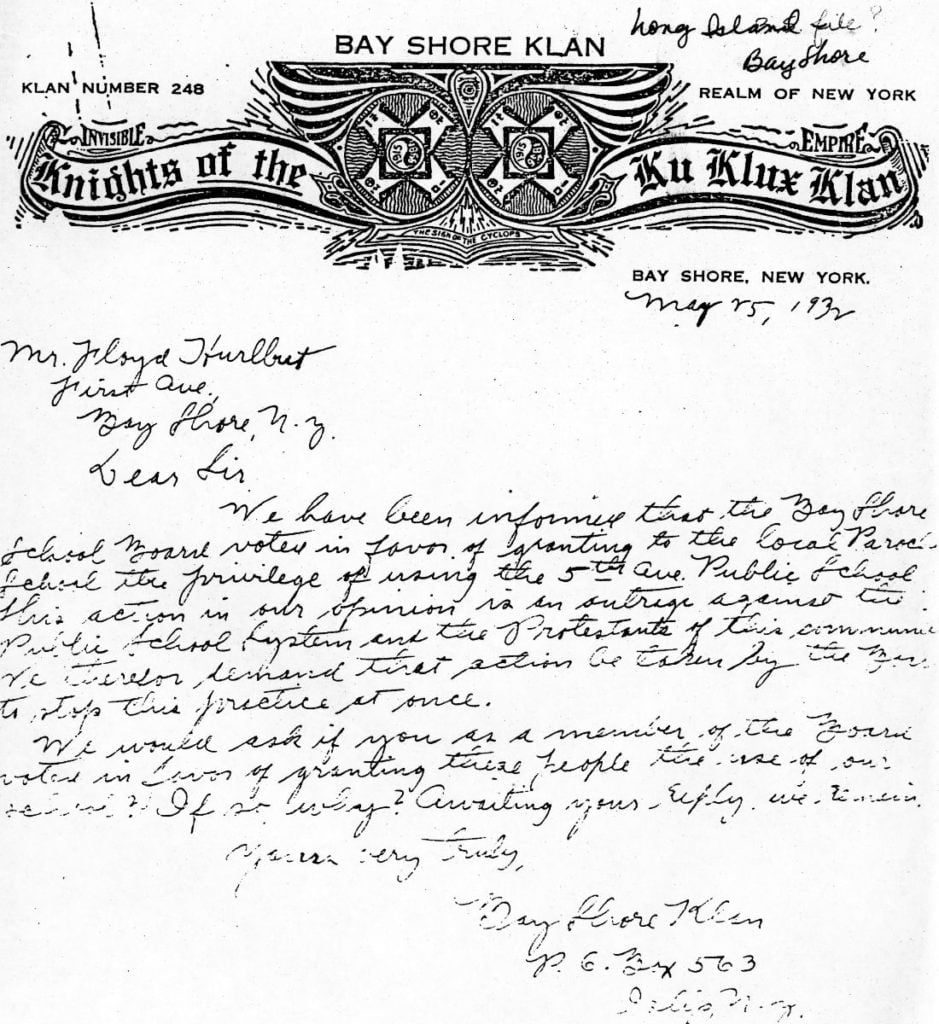

Klan-inspired newspapers, such as the Rail-Splitter, printed articles that claimed Catholics accumulated weapons in the columns of their churches and were conspiring to commit random acts of terrorism. These false news reports fueled membership of local Ku Klux Klan chapters across the South Shore. Suffolk Klan membership swelled to one in seven residents within the county.

In Bay Shore, community recruitment for potential Klan members faced stiff opposition from local Catholics and affiliated groups. On Nov. 7, 1922, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported that Imperial Klokard G.A. Mahoney of the Ku Klux Klan Atlanta Georgia chapter was to give a lecture in the Odd Fellow hall on recruitment.

Then on Nov. 9, thousands of protesters stormed the hall and threatened the Klan members. In response to the demonstrations, state troopers shut the meeting down to prevent violence. Some local store owners who were against the anti-Klan protest hung signs that read TWAK (Trade only with a Klansman) to demonstrate solidarity to the Klan members.

The Catholic and Klan tensions spilled over into Islip Town politics as well. Catholic groups started to endorse and hold public forums for town and county candidates. Democratic town supervisor James Richardson became favored by Father Donovan of St. Patrick’s Parish of Bay Shore. In response to the relationship the Catholics had with Richardson, Republican challenger, Frank Rogers, was endorsed by Klan leaders.

On June 24, 1923, the Holy Name Society held a rally in Bay Shore to bring awareness against the threat of intolerance toward Catholics. The demonstration against the Klan attracted an estimated 40,000 people. At the rally, Father Donovan introduced town supervisor James Richardson as a supporter of the community.

However inspiring, the rally yielded short-term negative results; it served as the extra push the Klan needed to build a political coalition. That November, Rogers defeated Richardson by four votes, and Klan-backed candidates took control of all town offices.

On Nov. 9, 1923, the Ku Klux Klan had a victory parade in Bay Shore to celebrate the election results.

An estimated 350 members marched in full Klan uniform while holding a giant cross illuminating with battery operated lights. Fear gripped the Catholic community.

But that fear would give way.

There’s strength in numbers, and an ever-expanding Catholic population prevented any anti-Catholic sentiment from becoming actual, restrictive law. In the early 30s, the continuing demographic shift pushed the Klan back into the shadows as embarrassing relics of intolerance.

Sources: The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Klokards, Kleagles, Kludds, and Kluxers: The Ku Klux Klan in Suffolk County, 1915-1928, Part One, By Jane S. Gombieski, Fall 1993 Volume 6 * Number 1 copyright 1993 by the Long Island Historical Journal