Click here for Greater Long Island newsletters. Click here to download the iPhone app. Or follow Greater Moriches on Instagram.

For more than two decades, researchers at Brookhaven National Laboratory’s particle accelerator have recreated conditions similar to those at the beginning of the universe. Now, the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider is entering a new phase aimed at unlocking even more of its secrets.

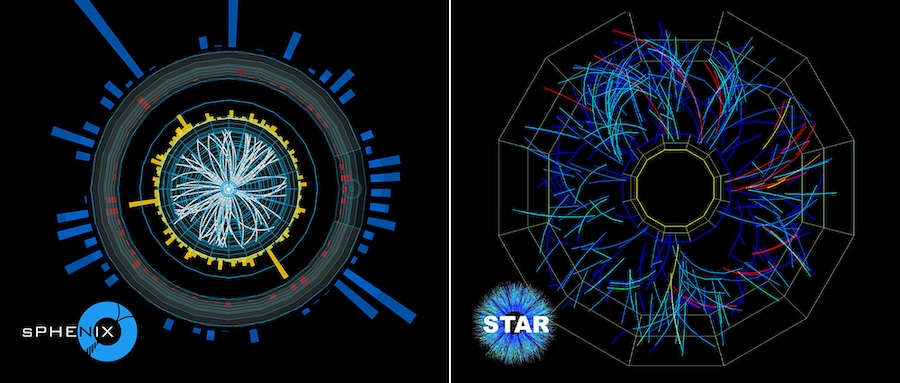

Just after 9 a.m. on Feb. 6, the final beams of oxygen ions — oxygen atoms stripped of their electrons — circulated through two 2.4-mile-circumference rings and slammed into one another at nearly the speed of light. The last collisions capped a quarter century of experiments involving 10 different atomic species across a wide range of energies and configurations.

Over its lifetime, the collider produced discoveries about the building blocks of matter, the nature of proton spin, and technological advances in accelerators, detectors and computing.

“We’re here to turn off the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider and it’s really humbling to think about that and what it’s achieved,” said John Hill, interim director of the laboratory, minutes before the accelerator shut off.

Hill said the primary function of the collider was to smash atomic nuclei to near light speed to observe what would happen and better understand what the early universe was like. Since 2000, roughly 300 trillion particle collisions have taken place, generating hundreds of petabytes of data.

The collider successfully recreated quark-gluon plasma, an ultra-hot, ultra-dense “soup” formed by melting protons and neutrons at temperatures of trillions of degrees Celsius. Scientists believe this state existed microseconds after the Big Bang.

“It’s success, collaboration from the Department of Energy, from congress, from the scientific community, from the local community — thousands of thousands of people were involved in the years in making this machine,” Hill said.

Counting down from five, Dario Gil, under secretary for science at the U.S. Department of Energy, prepared to press a large red button — as monitors displayed live data from the particle collisions — to shut the collider down for the final time. After the group reached one, the button was pressed and data collection stopped.

“Now, RHIC is over. Its operation is complete,” Hill said. “The science will continue, but today marks the end of data collection. We’re here to celebrate that success story.”

The next phase of particle acceleration

“Now we come to a bitter sweet day. We just closed our last operation — last collision — and we’re going to transform this wonderful collider into a new one with a bright future ahead for the next 25 to 30 years,” said Abhay Deshpande, associate laboratory director for nuclear and particle physics at the laboratory.

The Electron-Ion Collider will build on the current machine with several major modifications. A new electron storage ring will be constructed inside the existing tunnel so collisions can occur where the ion and electron beams cross.

When electrons collide with ions in the new collider, the interactions will be captured by a brand-new detector. Instead of recreating the early universe, scientists say the microscope-like measurements will reveal how quarks and gluons are organized and interact within the matter that makes up today’s world.

Deshpande compared the old collider to smashing two watermelons together and “trying to see what happens.” The new collider, he said, will be like driving a knife into a watermelon, allowing researchers to view the internal structure of particles far more clearly. The work will help scientists understand how quark-gluon matter transitions into protons.

“The EIC brings immense precision and control over what you want to see inside,” Deshpande said.

The new collider could also help answer three Nobel Prize-worthy questions, including how nearly massless quarks and gluons generate the mass of visible matter, how proton spin is influenced by quarks and gluons, and the nature of the gluons that “glue” matter together and create the strongest force in nature.

“It’s going to be very challenging, but also exciting,” said Daniel Marx, one of the accelerator physicists working on the design of the new collider. “We’ll be doing things that have never been done before.”

Researchers say the facility could lead to advances in cancer detection and treatment, computer chip testing, drug development and battery design.

“It will not only significantly enhance our knowledge of fundamental science, but it will be helpful for health, medicine, accelerators, AI computational tools, energy, national security, and workforce development,” Deshpande said.

Deshpande called the project the future of nuclear physics in the United States and said it will help keep the country at the forefront of the field.

The new collider will be funded primarily by the DOE Office of Science and is expected to become operational in the early to mid-2030s.

Top: Darío Gil, the U.S. Department of Energy’s Under Secretary for Science, right, and John Hill, interim laboratory director at Brookhaven Laboratory, officially ended the operational run of the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider Feb. 6. Photo courtesy of Kevin Coughlin/Brookhaven National Laboratory.