OUR SPONSOR

Greater Bay Shore coverage is funded in part by Shoregate, now leasing brand-new premium apartment homes in the heart of Bay Shore. Click here to schedule a tour.

by Christopher Verga |

Forty-four miles from New York City’s congestion and exhaust-filled streets sits a 32-mile sandy beach island oasis.

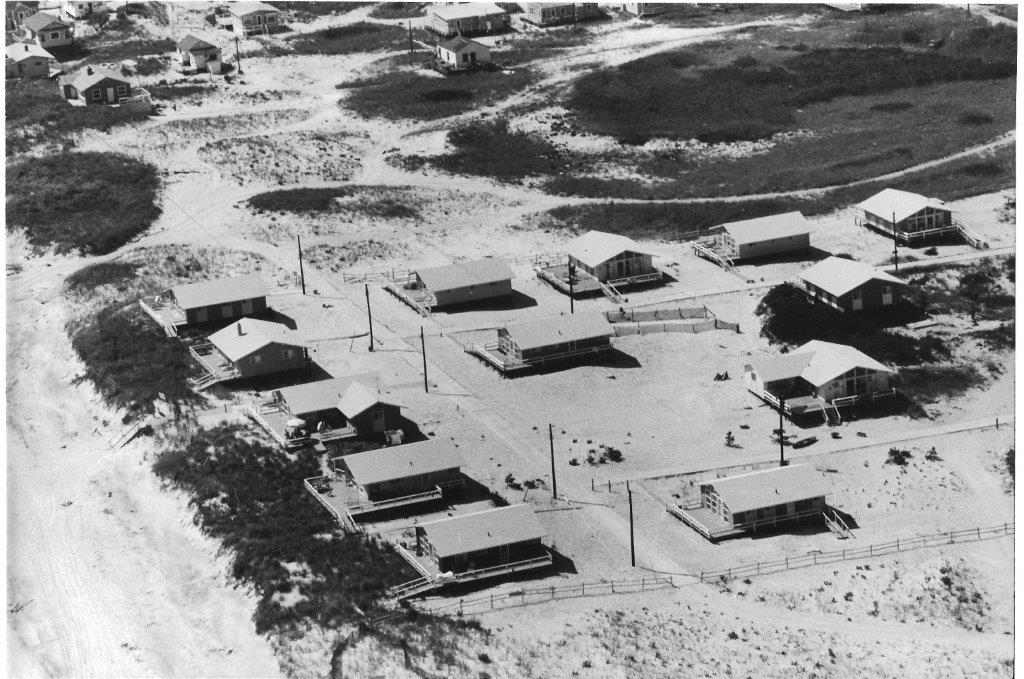

Distinct from Long Island’s mainland, Fire Island is home to 17 communities that vary in identity.

Lifestyles that shape these communities differ greatly, from Bohemians, to well-to-do Madison Avenue executives, to White Anglo-Saxon blue bloods, to hospitality workers and blue-collar laborers.

Though isolated from one another through their differences, they’ve all prided themselves on access to the ocean beach — and limited access to automobiles.

These communities are all built around pedestrian friendly towns nestled within barrier island vegetation. It’s been love at first site for so many vacationers.

Despite this, the Fire Island that we all know was slated to become a memory.

With the expansion of post-World War II suburban Long Island, all of the towns and hamlets were being developed (or redeveloped) around the idea of automobile accessibility. The last part of Long Island untouched by parkways was Fire Island.

Top Photo: Looking east from Fire Island Lighthouse. (Credit: Mike Busch/fireislandandbeyond.com.)

Master builder Robert Moses, responsible for shaping much of NYC and Long Island into what it is today, had first proposed a highway through Fire Island after the 1938 hurricane season.

His argument was that a highway would secure the barrier island and prevent coastal erosion from hurricanes. Construction of the highway would require hundreds of homes to be demolished. Resistance from locals shelved the project until 1962’s coastal storms.

column continues below photo

After the 1962 hurricane and winter storm season, which saw many homes lost to sea, the planned highway was back on track for construction.

With the memory of the 1962 storms still fresh, and the communities of Fire Island so fragmented, a planned highway should have had little opposition. The only obstacle was the homes of the 35,000 summer and year-long residents that lived, in many ways, isolated from one another.

Moses, unaware of the commonality of residents’ sheer love for the island and island life, did not anticipate any unification, political pressure or lawsuits to delay his projects.

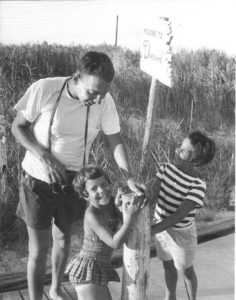

Then Maurice Barbash of Brightwaters, builder of the Dunewood community near Fair Harbor, and his brother in-law Irving Like, a lawyer, organized the Citizen’s Committee for a Fire Island National Seashore. Members of this grassroots group began to collaborate with the League of Women Voters, chambers of commerces from across the South Shore, and various mainland environmental and civic organizations.

Participation in letter-writing campaigns, town hall meetings and phone calls to elected officials was fueled from the growing environmental concerns among county residents. Suburban development was eroding the cherished oak and pine forests for housing developments, strip malls and highways. Fire Island would not be an exception.

As a result of the community efforts, on August 20, 1962 H.R. 12965 was voted on and passed in the House of Representatives.

This bill established the National Seashore of Fire Island. In 1964 President Lyndon B Johnson signed the bill into law, which created the National Seashore and halted development of any proposed highway, which would have run east from what today is Robert Moses State Park.

Moses had also argued, and it was endorsed by many locally elected officials and local newspapers, that the highway through Fire Island would be an economic boom.

The boom happened anyway.

Today, the economic and social identity of Babylon, Bay Shore, Sayville, and Patchogue are shaped through the preservation of the National Seashore and its 17 communities.

According to the National Park Service, just under 500,000 people visit Fire Island each year, and spend an average of 19 million dollars across all the local Fire Island villages.

Tourism as a whole for the National Park Service generates $10 for every one dollar the agency spends on upkeep of the parks.

This revenue and intellectual capital that’s generated through the island is reinvested and distributed throughout the South Shore of Long Island, making it an increasingly attractive place to live and work.

Sources:

Interviews from Susan Barbash, Irving Like and Lee Koppelman

NYT: Maurice Barbash, Who Saved Fire Island’s Terrain, Dies at 88

NPS: Tourism to Fire Island National Seashore creates $19,258,500 in Economic Benefit