OUR SPONSOR

Greater Bay Shore coverage is funded in part by Shoregate, now leasing brand-new premium apartment homes in the heart of Bay Shore. Click here to schedule a tour.

by Christopher Verga |

by Christopher Verga |

Millions of people have visited Fire Island over the centuries for its sandy beaches, picturesque landscapes and crashing waves.

But these people were headed to Fire Island not to relax, but because of possible exposure to the highly contagious and deadly bacteria cholera.

And they had Long Islanders on edge.

Transmitted through food or drinking water, Cholera can have a mortality rate of up to 70 percent. And in late August of 1892, Hamburg Germany was in the midst of a cholera epidemic, with an average mortality rate of three deaths per every five cases.

Fifty years earlier, this would have not caused any concern in New York, but 1890’s America was becoming the center of a growing global economy and steamliners were routinely traveling from Hamburg to New York.

Liners Moravia, Normania, Rugia and Scandia were the last ships to leave Hamburg before the outbreak reached epidemic levels. Leaving three days prior to the other three boats, the Moravia’s passengers had four deaths related to cholera within the first 16 hours at sea.

In response to the potentially contaminated crew, New York’s governor at the time, Roswell Flower ordered the passengers quarantined once they reached New York waters.

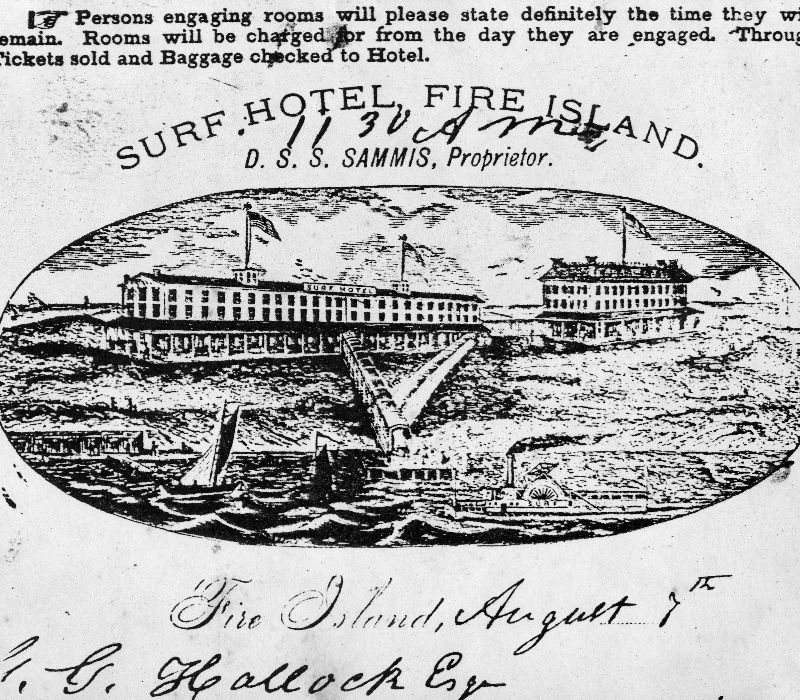

Dr. Cyrus Edson and Charles Wilson of the New York State health department set out to designate emergency quarantine stations away from dense populations. The Surf Hotel on Fire Island was singled out as an ideal location due to the isolation and its ability to house up to 1,000 people.

In a secret, closed-door meeting with Governor Flower and hotel owner David Sammis, they reached an agreement for the state to pay $210,000 with $50,000 upfront for use of the property.

The secret meeting and the arrangements were leaked to the public. Baymen that lived in the surrounding area had orders of shellfish canceled due to the fear of contamination.

Islip’s largest oyster harvester, Charles Oacus lost up to $40,000 in contracts within three days.

From Babylon, to Patchogue, an estimated 5,000 to 6,0000 people who were employed through fishing and charter boats were at risk of job loss.

Islip Town officials filed an injunction to prevent any contaminated boat from landing on or near Fire Island. Islip Town Supervisor W.H. Young ordered 20 armed deputy constables to Fire Island to enforce the injunction. The following day, the State Supreme Court vacated the injunction.

In response, 267 mostly women and children were transferred from the Normania liner to the steam ship Cepheus (pictured above), which was bound for Fire Island.

The governor ordered the Fire Island Saving Station to help navigate the Cepheus around the sand bars to dock. Station supervisor Arthur Dominy refused the order and threatened his crew with termination if they complied with the state.

Throughout the night, 300-400 baymen landed on Fire Island to block access to the docks and to burn down the Surf Hotel.

To restore order and carry out the docking of the Cepheus, Governor Flower called in the 13th and 69th Army regiments and naval reserves.

After days of resistance, the passengers were loaded into the hotel.

Newspapers from San Francisco to New Hampshire reported the local resistance and patiently waited for a cholera epidemic of biblical proportions.

It never happened.

After two to three weeks, at-risk passengers were released back into their day-to-day lives.

Resources:

Resources:– The Suffolk County News September 24, 1892

– Daily St. Paul Globe (Minnesota) September 12, 1892

– Democrat Chronicle (Rochester NY) September 12, 1892

– The Philadelphia Inquirer September 12, 1892

– Brooklyn Daily Eagle September 12-13, 1892

The picture of the ship Cepheus is courtesy of Library of Congress picture collection

The Surf Hotel postcard courtesy of Bay Shore Historical Society