Greater Bay Shore coverage is funded in part by Shoregate, now leasing brand-new premium apartment homes in the heart of Bay Shore. Click here to schedule a tour.

It was the dawn of 1860, and Long Island and New York City were in transition.

Struggling to economically adapt to a free-falling whaling industry became a challenge for islanders.

Whales were becoming scarcer, and the industrial revolution introduced cheaper alternatives to whale-based products.

Despite the decrease of whaling, the shellfish industry was generating millions of dollars yearly, similar to any economy evolving: there are winners and losers, and high unemployment.

Captain George Hanford Burr of Bay Shore was on track to be one of the winners of the budding shellfish industry.

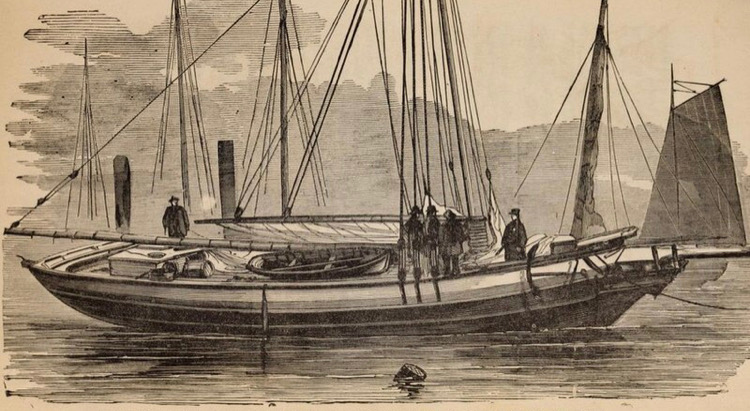

Captain Burr, working his way up from deckhand to captain became a co-owner of the schooner, the E.A. Johnson.

The schooner was outfitted with a crew of two other deck hands, Smith and Oliver Watts of Islip.

The Watts brothers were stepsons to Lorenzo Hubbard, who was a descendant of Islip Town’s earliest residents.

When not at sea, Burr and the Watts brothers were active members of United Methodist Church of Bay Shore and were fixtures among social circles.

In March of 1860, the simple small-town life of these men would become immortalized throughout every newspaper in the country.

Their claim to fame would be that they were the last documented victims of New York piracy.

Albert Hicks, also known as William Johnson, was an unemployed whaler who turned bandit. Hicks supported his family by looting boats.

Unlike the historic pirates of the 17th century, Hicks was a one-man operation.

In March of 1860, Hicks got a job on the E.A. Johnson sloop under his alias, William Johnson.

After a couple weeks working on the sloop, Captain Burrs brought Hicks to his Bay Shore home to dine and meet his family.

While building these bonds of trust, Hicks learned of some monetary reserves, which were stowed on the sloop.

On the night of March 20, the E.A. Johnson was sailing along the coast of Staten Island on course to harvest an oyster bed in the Carolinas.

Between 9:30 and 10:00 p.m., Oliver Watts was navigating the ship as the other two crew members, Captain Burrs and Smith Watts, were napping.

Hicks came up to the helm with a hatchet and asked Oliver if he saw the Barnegat Light of Sandy Hook, N.J.

While his head was turned, Hicks buried the hatchet into Oliver’s head.

story continues below E.A Johnson image

Upon hearing the noise, Smith ran onto the deck. Hicks took one swing of the hatchet and took Smith’s head off.

After killing both brothers, Hicks picked up a marlin spike and stabbed to death a sleeping Captain Burr.

All the bodies were dumped overboard and Hicks took cash reserves of $150 and left the ship for the mainland.

Following a two state manhunt, Hicks was caught and brought back to New York for trial.

New York City’s conviction rate for murder was less than 40 percent.

The district attorney, wanting to build a stronger case, tried Hicks on piracy, which carried a death sentence.

On June 2, the jury rendered a guilty verdict and Hicks was sentenced to be hanged on Friday, July 13, on Bedloe Island (current day Liberty Island).

In the coming days of his execution, Hicks confessed to over 100 murders on merchant and whaling ships.

Hicks explained that he went to California, Louisiana and New York ports by getting work on boats, killing everyone on board the boats and robbing the boat of its valuables.

These confessions and the details on the stolen goods solved various murders.

The infamous life and execution of Albert Hicks marked the last trial of piracy in New York.

We tend to romanticize the life of pirates such as Albert Hicks, living as an anti-establishment nomad thus keeping his legend of alive.

At the same time, this historical view further victimizes the Watts brothers and Captain Burrs to suffer a second death of being forgotten.

Sources: The Pirate Albert Hicks from The Murders at Sea: March 29, 1860, The New York Times, Page 8. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 2, 1860