Greater Long Island coverage is funded in part by Toresco & Simonelli, a boutique injury and family law firm in West Islip. They fight for their clients. Click here to get in touch.

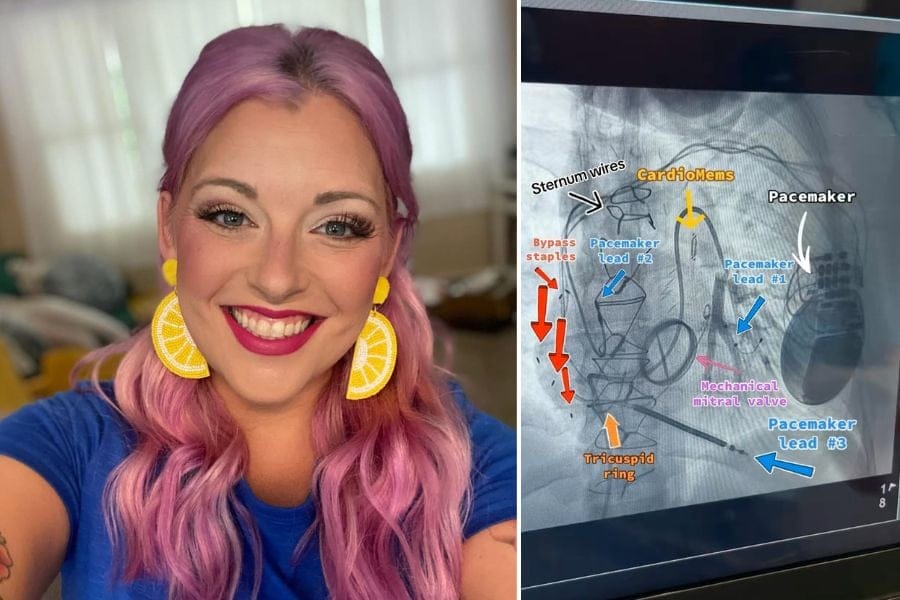

On an X-ray, Alicia Nicoletti’s chest looks less like a ribcage and more like a junk drawer.

“You should see it,” she said, laughing through the description. “I’ve got the pacemaker, the CardioMEMS, all the wires looping all over the place. Then there are the rings from my mitral and tricuspid valves, and the wires in my sternum that literally look like twist ties — you know, the kind you’d shove in a kitchen drawer and never use. And staples from my bypass. It’s wild. It’s totally a junk drawer.”

That junk drawer has kept Nicoletti alive for nearly two decades.

Her story resonates especially now, with World Heart Day being observed this Monday. She is a living example of the importance of heart health worldwide.

A fateful morning in 2006

In January 2006, then 22-year-old Alicia Pellegrino (her maiden name) dropped a friend off at work early in the morning and began driving home. Exhausted, she fell asleep at the wheel and struck a school bus head-on.

Fortunately, no children were aboard. First responders rushed her to a nearby hospital, where at first glance, doctors thought her worst injury was a bloody nose.

In truth, her right coronary artery had been severed. Her mitral valve had ruptured. She had torn tissue between chambers of her heart and was in full cardiac arrest.

Her three sisters — two her triplets and the other just 21 months older — were pulled into a hospital room and handed pamphlets on how to deal with the death of a young person.

“I don’t remember any of this, but they do,” Nicoletti told Greater Long Island. “For them, it was worse than it was for me. They had to live it. I was unconscious.”

She was transferred to another hospital for emergency open-heart surgery. Her family was told she might not survive the ride to the next hospital. But against all odds, she lived.

Before and after

Nicoletti, now 41, often describes her life in two halves: before the accident, and after.

Before, she was a Bay Shore native who attended St. John the Baptist Diocesan High School in West Islip and later Stony Brook University. She was captain of the high school cheerleading team, the lead in the school play — always performing, always moving. She worked at a gymnastics facility teaching children and was focused on earning her college degree.

After the wreck, everything changed.

The life she planned on having “ended up not being my life at all,” she said.

Nicoletti met her husband John — “everyone calls him Johnny” — about six months after the crash. They married in 2011 and live in Wantagh.

John Nicoletti is an X-ray technologist at a major Long Island hospital. The couple had hoped for children, but Alicia’s heart conditions make that impossible.

“I can’t work, I can’t climb a flight of stairs without paying for it,” she said. “But I am alive. And that’s everything.”

A long road

Survival hardly marked the end of Nicoletti’s ordeal. Rather, it was the beginning of a marathon.

Over the years, she endured more than a dozen ablations to treat arrhythmia, multiple pacemaker surgeries, valve repairs and replacements, and several open-heart operations.

In her mid-30s, she was diagnosed with heart failure — the very condition she would look at posters for in her cardiologist’s office and think, “Well, at least I don’t have that.”

“It was like a punch to the gut,” she said. “After everything I’d been through, to hear those words — heart failure — I thought, this is what’s going to kill me.”

Her doctor told her to stop working if she wanted to see 40. Immediately, she left a job she loved in medical billing and data analysis.

Technology and travel

Nicoletti’s outlook shifted with the Abbott CardioMEMS system. Surgeons implanted a small device — the size of a small paper clip — in her artery that sends real-time data to her Catholic Health physicians via a special pillow she lies on every morning. The system allows her doctors to tweak her medications before symptoms worsen or kick in.

“It’s like testing your blood sugar if you have diabetes,” she said. “Why wouldn’t you want to watch your disease?”

The device gave her freedom.

She could say ‘yes’ when her niece asked her to dance at a bluegrass concert and she could take road trips with her husband and family. Last spring, she visited Zion, Bryce Canyon, and the Grand Canyon — adventures she thought she’d never live to see.

“I didn’t have to think of everything as a compromise anymore,” she said. “It gave me back control.”

Living with limits

Nicoletti’s days are still shaped by her illness. She cannot lift more than five pounds. She follows a strict diet and takes “no less than a million pills a day.” Even climbing stairs or standing too long requires days of recovery.

But she insists on color and joy. Her hair is pink, tattoos trace her arms, and humor fills her hospital stays, often with her sisters at her side.

“They were just happy I was there, alive,” she said. “How could I be upset about all the things I was connected to or the fact that I had to roll onto a bedpan to go to the bathroom.”

Writing her story

Now 41, Nicoletti is writing a book about her journey. She has already had short stories published, including in the Kurt Vonnegut Memorial Museum’s journal.

She also travels to speak as a patient ambassador, hoping her story helps others living with chronic illness.

“I hate the saying that everything happens for a reason,” she said. “I don’t believe I was thrown in front of a bus for a reason.

“But I do believe we get to decide what we do with what happens to us,” she continued. “If I can take all of this and use it to help someone else, then maybe it’s okay that it happened.”

World Heart Day message

With World Heart Day approaching, Nicoletti’s message is clear: don’t wait.

“People don’t think about their heart until something goes wrong,” she said. “But heart health can be protected, and if something does happen, you can still live with it. That’s what I want people to know.”

From a junk drawer chest of wires and valves, Nicoletti has found her purpose — a living reminder of both fragility and resilience.