Once a summer paradise, Lake Ronkonkoma is in trouble, and it has nothing to do with Native American folklore. Locals say saving it will take unity — and urgency.

On a bright summer morning, sunlight still dances across Lake Ronkonkoma’s surface. The breeze carries echoes of laughter that once filled the air — from divers, dancers, and families escaping the city heat.

But beneath that glittering calm, Long Island’s largest freshwater lake is in trouble.

Decades of runoff, neglect, and political gridlock have turned this former resort paradise into one of the Island’s most polluted bodies of water.

The fight to save it has become as murky as the lake itself.

A resort built around the water

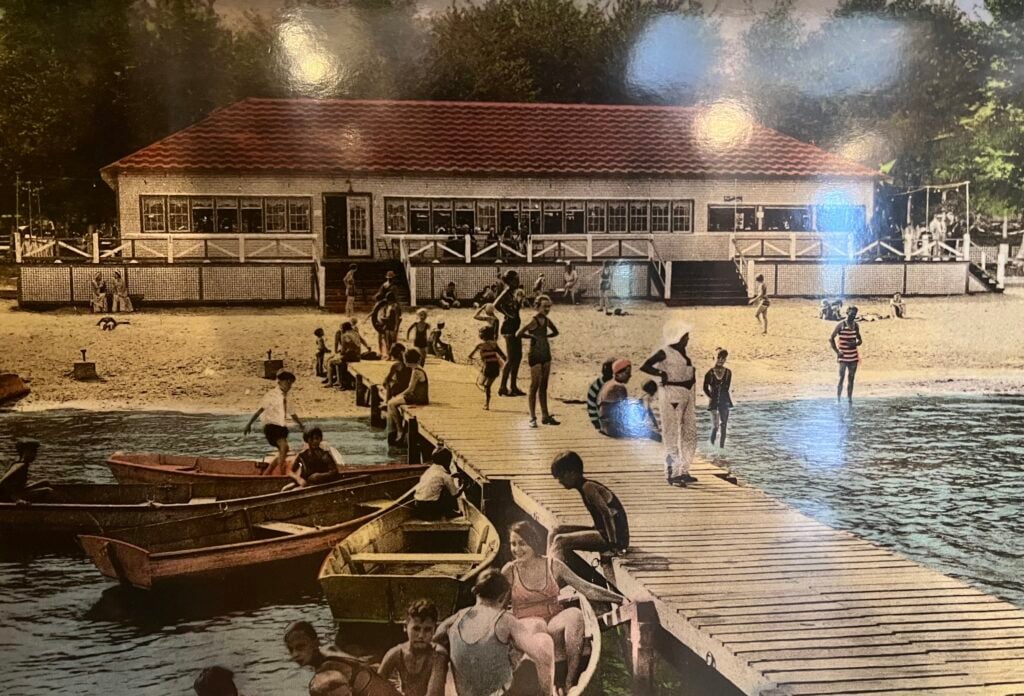

Huge waterslides, diving boards and motorboats once dominated Lake Ronkonkoma — a century ago, it was a resort town that rivaled any in the Northeast. Pavilions, hotels, inns, restaurants and casinos drew visitors from across Long Island and the boroughs.

During the lake’s golden era in the late 1800s through the mid-1900s, people flocked to its more than a dozen public and private beaches.

They swam, fished and danced the summers away on its shores.

“The residents started to realize that there were very affluent people coming and they were building homes,” said Evelyn Vollgraff, president of the Lake Ronkonkoma Historical Society.

“That’s how the heyday actually started,” she said. “You had your rich people who realized that they could build these beautiful homes here and there was no income tax at that time, so they had a lot of money.”

The well-heeled would also lodge at places like the The Gables Hotel Casino, which was situated on 34 acres on the lakeshore. That hotel burned down in 1896 and was replaced by the Lake Front Hotel, “where many guests stayed and social events for the summer visitors took place,” reads the Ronkonkoma Chamber of Commerce website.

In response, locals built pavilions and beaches of their own — like Raymond Duffield’s West Park Beach in the Town of Islip, where he sold food, drinks and towels. That area turned into a huge social scene that stayed very much active through the late 1950s.

“This is the beach I enjoyed my entire childhood, and as a teenager I danced in the pavilion till my feet were sore,” wrote one Facebook commenter, Fran Garafola, on a Lake Ronkonoma Historical Society post from 2014. “Rock Around The Clock” from the jukebox [sic]. Love to remember…”

“Got married there in 1957,” wrote another commenter, June Melody. “So beautiful.”

On the southeast side, George Raynor in 1921 turned his estate into what would become Raynor Beach County Park, complete with bathhouses, waterslides and a dock.

“It was a big, big amusement park area,” Vollgraff said. “Unfortunately, it’s all gone.”

The lake before people

Lake Ronkonkoma’s story began more than 25,000 years ago, when retreating glaciers carved the land that became Long Island. As the ice melted, giant chunks broke off, leaving depressions that filled with water — known as kettle lakes.

Ronkonkoma became the largest of them all, spanning 243 acres, about three-quarters of a mile wide and up to 65 feet deep in some areas.

The four nations of the lake

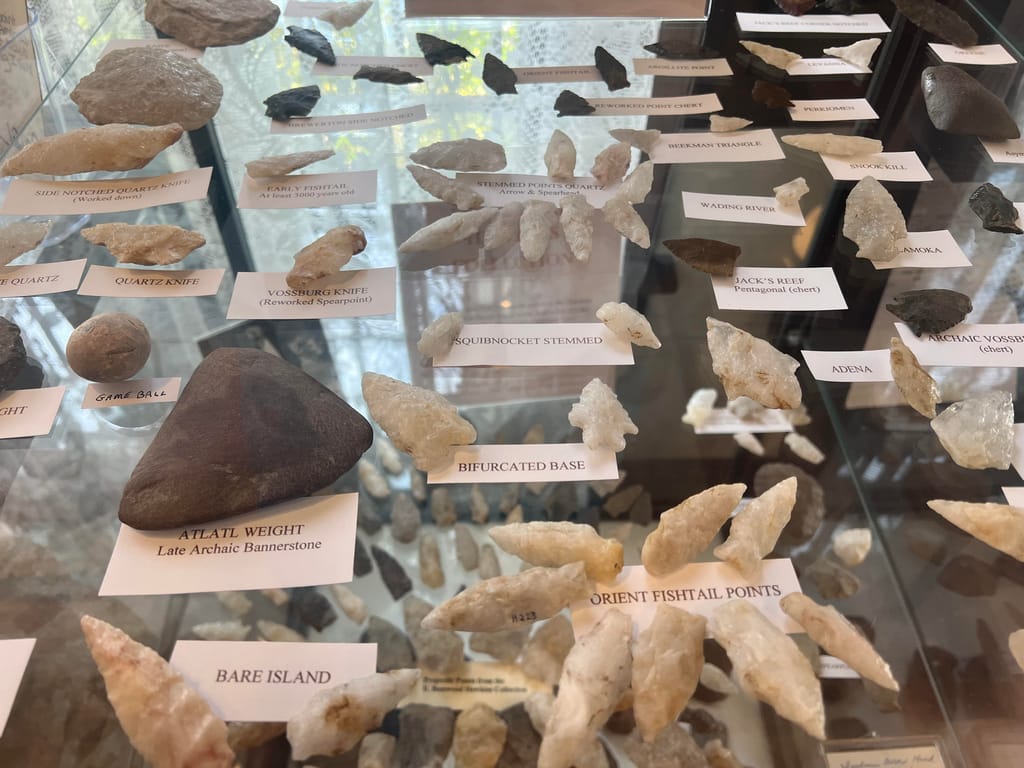

Thousands of years before the resort era, four Native American nations — the Setaukets, Nissequogues, Secatogs, and Unkechaugs — lived around the lake.

“12,000 years ago, the sea level was much lower,” said Scott Kostiw, author of The Archaeology of Long Island from the Paleoindian to Contact Periods. “So the Native Americans were able to cross over from Connecticut to Long Island, walking over what is now the Long Island Sound.”

They hunted deer and small game, fished, and gathered nuts and berries along the shore.

The name Ronkonkoma comes from the Algonquin phrase meaning “boundary fishing place,” a reflection of the peace that existed among the four nations who treated it as neutral ground, avoiding quarrels for a greater, shared good.

The first settlers

In the 1650s and 1660s, the four nations began selling their land to English settlers.

According to the Ronkonkoma Chamber of Commerce, the Setaukets were the first, selling their land for items that included coats, kettles, wampum, powder and knives. Even a pair of stockings for a child was thrown in the mix.

“The Indians retained the right to hunt, fish, and in some instances, live on the land,” the chamber’s website reads. “It is doubtful that the Indians really understood the meaning of the sale since they had no concept of individual ownership of land as practiced by white men.” (Many Native Americans also died of disease or assimilated into English and Dutch culture.)

Because the lake bordered several native settlements, its eventual English ownership became divided. The purchases from the natives were not legally recognized at first, but the British crown would eventually grant patents to early settlers like William Nicholl of Islip, Richard Bull Smith of Smithtown and Richard Woodhull (and others) of Brookhaven.

“Islip, Smithtown, and Brookhaven formed separate townships with the right to purchase land beginning at the shoreline of Lake Ronkonkoma,” according to the chamber. “This precluded the possibility of ever having a single community with the lake as its natural center.”

That division — lines drawn more than 350 years ago — still affects the lake today.

The lake’s golden age

By the mid-1800s, the arrival of the railroad brought crowds to the water. Lakeland Station opened in 1843, replaced decades later by the Ronkonkoma Station, giving people from out west and the city easy access to the lake’s beaches.

During that period, urban residents sought to escape pollution — mainly from poor sewage and sanitation — heat and overcrowding in New York and Brooklyn (which didn’t incorporate until 1898). Lake Ronkonkoma’s fresh water offered relief.

Soon the shoreline was lined with homes, inns, and entertainment halls. Visitors enjoyed canoeing, kayaking, motorboating (eventually), ice boating in the winter, duck hunting in the fall. Lake tours were offered on a boat called Dark Cloud.

Lake Ronkonkoma would evolve into a year-round retreat.

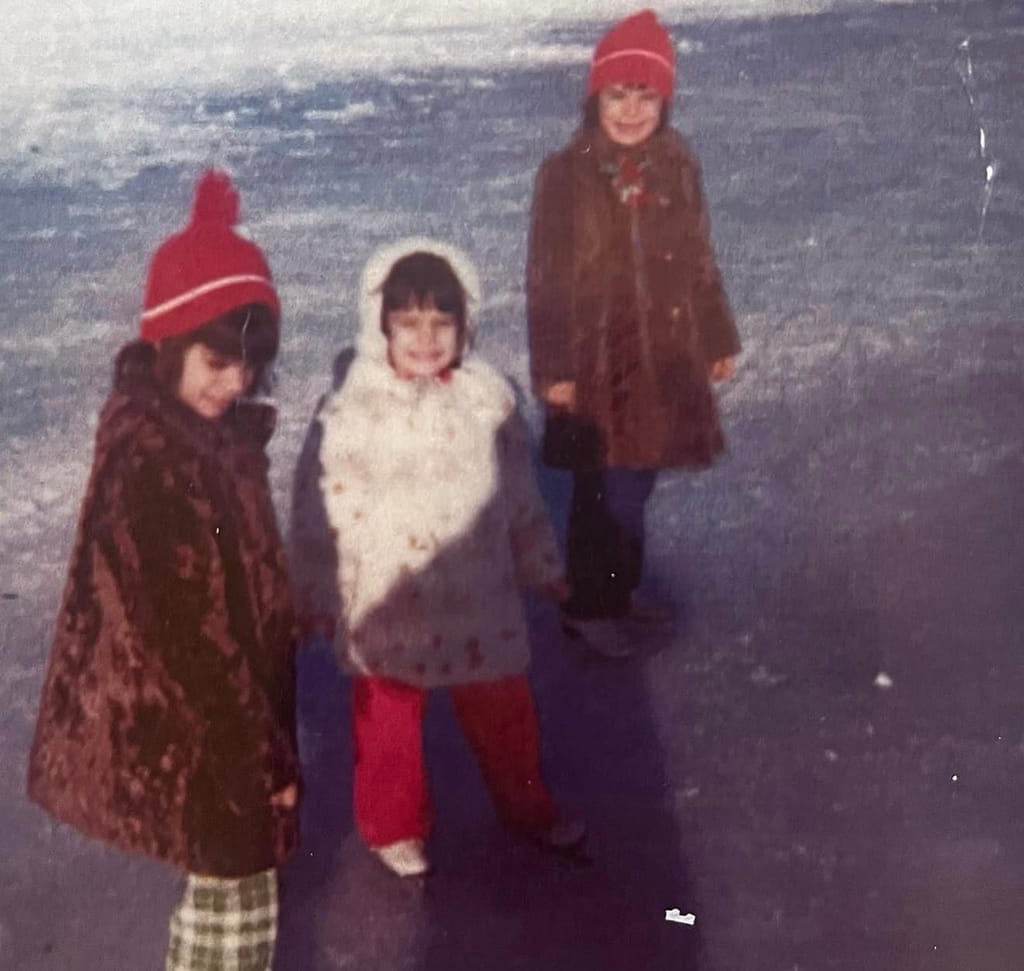

Lake Ronkonkoma native and filmmaker Maria Capp shared photos of her family enjoying the lake throughout the 1970s — in both winter and summer. She later went on to write and film “The Lady of the Lake,” a psychological thriller that delves into the lake’s haunted past.

The downfall

As roads and railways stretched farther east, travelers began exploring beyond the lake, such as the ocean beaches. The Great Depression and Prohibition followed, chipping away at what had been a thriving resort town.

“And that started the downfall of Lake Ronkonkoma,” Vollgraff said. “Little by little, all of that together, culminated in the lake’s demise.”

The pavilions became abandoned by the mid 1900s.

The decades-long run for Duffield’s West Park Beach ended at the close of the 1957 season. The Town of Islip acquired the Duffield property in 1959 and the area is now known as the Islip Town Beach, according to the Historical Society.

In 1960, a fire, started by arsonists, destroyed Raynor’s pavilion and a restaurant.

And in 1964, a controlled fire knocked down Green’s Pavillion at Hollywood Beach to make way for Brookhaven Town Beach (now known as Lt. Michael P. Murphy Memorial Beach). After that, the lake fell mostly silent.

A fractured shoreline

After the lake was largely abandoned, Suffolk County began buying property for parkland. The county currently owns 80 percent of the lakefront.

The rest of the beaches are broken up between different municipalities (see the graphic below): Starting from the bottom tip of the lake going clockwise, the Town of Brookhaven owns Lt. Michael P. Murphy Memorial Beach; the Town of Islip owns the floor of the lake and Ronkonkoma Beach; Suffolk County owns plots of land after Ronkonkoma Beach to Lake Ronkonkoma County Park; the Town of Smithtown owns plots of land after county park; and Suffolk County owns the land from the top of the lake all the way down the east side until it reaches Lt. Michael P. Murphy Memorial Beach.

There are some plots of land that are privately owned, like the Parsnip Lake House property. The Department of Environmental Conservation owns the boat ramp.

It’s a complicated map — and one that makes decision-making even harder.

Lake Ronkonkoma’s ownership

Toxic waters

As development spread, so did pollution. Runoff from homes and septic systems fed nitrogen and phosphorus into the water, encouraging the growth of toxic blue-green algae and invasive plants like hydrilla.

During warmer months, high bacteria levels frequently close the beaches.

“According to Suffolk County Commissioner of Health Dr. Gregson Pigott, bathing in bacteria-contaminated water can result in gastrointestinal illness, as well as infections of the eyes, ears, nose, and throat,” reads one recent summer press release announcing beach closures at Lake Ronkonkoma.

The effort to restore the lake

Groups like the Lake Ronkonkoma Inter-Municipal Organization and Lake Ronkonkoma Advisory Board are working to reverse the damage.

“Once a month, [county] Legislator Leslie Kennedy runs a meeting for the Lake Ronkonkoma Advisory Board,” explained Mark Salzano, vice president of the Lake Ronkonkoma Civic Organization. “Different municipalities along the lake are on the board and listen to the public, who pitch them ideas on how to clean the lake.”

Among the biggest challenges are the high levels of nitrogen and phosphates.

Proposals include underwater aeration systems that circulate the lake’s water, filtration systems around its edges to capture fertilizer and oil runoff, and upgrades to older septic systems in the area.

“People have pitched ideas to find ways to reduce [pollution] in the lake through a filtration system that would be built in the lake and would release bubbles,” Salzano said. “The bubbles would begin circulating the water in the lake and over time, that will wipe out the nitrogen and phosphates.”

He added that planting more greenery — shrubs and bushes — could help filter stormwater naturally.

Then there’s the geese.

“With no population around the lake, where only a few people are on the lake fishing at one time — and a few people down at the beach, the geese population is high and their droppings are all along the lake,” Salzano said. “This adds another element of pollution.”

He believes more visitors would help. “If more people visit the lake, the geese will be pushed away, which would clean the environment,” he said.

Complex problems, little agreement

Fixing Lake Ronkonkoma is complicated. Vollgraff and Salzano both point to the biggest obstacle: cooperation.

“You can’t get all these townships to agree,” Vollgraff said. “Even on the advisory board, you have Smithtown, Suffolk County, Brookhaven, and Islip all represented. Everybody’s represented, but nobody does anything.”

In 2023, then-Suffolk County Executive Steve Bellone announced plans to hire a lakekeeper to oversee cleanup efforts and secure grant money.

Those plans had issues from the start.

“The way the job description was written was ridiculous,” Vollgraff said. “They were going to pay you for the first year and then you were responsible to get grants for your income.”

Few people applied.

“So it never got done,” Vollgraff said. “We’re still fighting for that because I think the lakekeeper is very important.”

Vollgraff also said the advisory board is in talks with an unnamed company to be a “one-stop-shop” organization that’s focused on the lake’s health.

If that company could come up with a comprehensive plan, she said, the county would then seek grants to tackles the issues.

Update: A new hope for Lake Ronkonkoma as officials announce lakekeepers

A renewed hope

The meetings continue, and residents keep pushing for change.

“We want to revitalize it to a place where people can be comfortable to swim in the lake, bring some food trucks every once in a while, some kayaks, maybe a slide,” Salzano said. “Let’s get it back to where people appreciate the lake’s history and what it offers to our community.”

The work, he noted, is “complex.” And with the lake divided between the towns and county, real progress will depend on cooperation.

After all, Lake Ronkonkoma’s story began as shared ground — a place where people gathered, not divided.

The question now is whether it can be that again.

Follow up

Top: Historic photo of bathers and boaters enjoying the lake at Raynor’s Beach, foreground. (Courtesy of Lake Ronkonkoma Historical Society) Current photo of Lake Ronkonkoma taken Oct. 21, 20215. (Credit: Jessica Durso) Graphic by Nick Esposito